Hail, Holy Queen, Mother of Mercy

Our life, our sweetness and our hope.

To thee do we cry

Poor banished children of Eve.

To thee do we send up our sighs,

Mourning and weeping in this valley of tears.

Salve Regina

Over a one hundred year period a practice known as verdingen (indentured servitude) operated in Switzerland. Children were removed from their families and sent to work on farms. It is estimated that between 1860 and 1960, one hundred thousand children were verdingt in this way, a quarter of them in the Canton of Bern. Local parishes paid farmers a monthly allowance to provide disadvantaged children with board and lodging.

Although some treated their charges well, countless children suffered terrible hardship over many years. A veil of silence fell across entire communities as clergy, social workers and villagers chose to ignore the widespread abuse. Teachers who reported that children were being ill-treated often found that their contracts were not renewed at the end of the school year.

I was born in Switzerland and grew up in England. As an adult I lived, worked and raised a family in the town of Biel, near Bern. Yet, in all those years, I never heard mention of the Swiss Verdingkinder. It was not until April 2000 that I read an article in The Guardian titled The Vanishing.1 I mentioned it to my Swiss father-in-law, who told me that two half-brothers from his father’s first marriage had been verdingt when their mother died.

The youngest child, a girl, was not given away, and grew up with him and his brother in the second marriage. Something similar had happened in my own family. My grandmother, Rosa, was the only child of her father, Rudolf’s second marriage. She grew up with her half-sister Bertha, whose mother had died when she was three years old. Bertha never married and worked as a laundress at hotels on the French Riviera and in the sanatoriums of Davos.

My mother and I used to visit Aunt Bertha in Basel before we boarded the night train to Calais. Her apartment was crowded with sofas and ottomans, upholstered in shades of olive and tobacco velvet and everything was bathed in a warm, butter-yellow light.

My grandmother, Rosa as a child in the arms of her father, Benedicht Gilomen, her mother Anna-Maria, and Rosa’s paternal grandfather. They are standing in front of the family farmhouse in Scheunenberg, Canton Bern, Switzerland, 1889.

Bertha Gilomen died in 1966 and my mother, Lea and her brother, Bobi were named as the sole heirs in her handwritten will. The lawyer’s will, however, listed twenty-three family members, all of whom were making a claim on my great-aunt’s estate. In a letter to Lea, Bobi wrote: I had no idea that any of these people existed. I was astonished by this remark. How is it possible for so many people from one family to vanish from living memory?

I returned to the Gilomen family tree in search of clues. Bertha and Rosa’s father was married for thirteen years to his first wife and she gave birth to six children before she died in 1885. What became of Bertha’s five siblings?

I have found that it is extremely difficult to conduct genealogical research in Switzerland. There is no equivalent to www.ancestry.com and the Bernese State Department carefully monitors and controls all documented information. Swiss passport holders may visit the archives three times a year, although there are no copying facilities available and photography is forbidden. In 1997 I telephoned the parish of Hoechstetten in Bern and requested a copy of my grandfather’s death certificate.

There was a moment of silence, followed by an audible intake of breath, and I was informed that such information was not available. Death, the woman told me in a tone of undisguised indignation, is a strictly personal matter.

There is a fine line between privacy and secrecy in Switzerland. Sixty-five percent of the country is mountainous, and this, in many ways, has shaped the sociology of its people. Communities are often isolated from one another and survival, especially in winter, requires a resilient and resourceful nature. People work hard and are wary of outsiders.

The village of Adelboden in the Bernese Oberland is where my mother went skiing when she was a young girl and it is where, in 1959, I was christened in the village church. During my childhood we spent every Christmas holiday in Adelboden, together with Uncle Bobi, Aunt Heidi and my cousin, Christine.

The Chalet Marlis is still offered as a holiday let and in 2015, I decided to spend a week there while I investigated the mystery of Aunt Bertha’s lost siblings. In Stauffacher’s bookshop in Bern I came across Versorgt und vergessen 2 (Filed away and forgotten) an oral history, documenting the experiences of forty former Verdingkinder. The stories were compiled and published in 2008 by Swiss historians, Marco Leuenberger and Loretta Seglias.

In our early years in Adelboden, I stayed with my aunt and uncle and my parents were guests at the Hotel Schoenegg. At some point, my teenage cousin began to resent sharing her room with an eight-year old and so, in the winter of 1967, I was sent to the local children’s home.

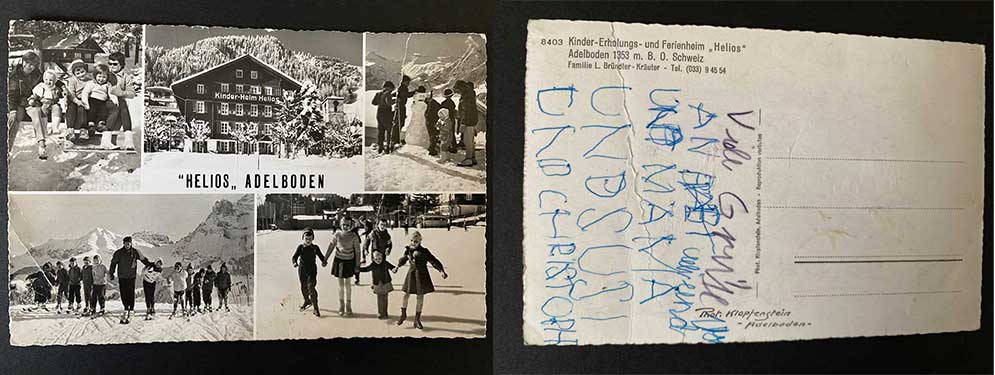

The Kinderheim Helios was a dark and gloomy chalet and I wasn’t at all convinced by my parents’ assurances that it would be huge fun living with lots of other children. Every day we would load our skis onto a sledge pulled by a donkey and walk through the village. If I saw Mum and Dad, I could wave but I wasn’t allowed to speak to them. I knew nothing about the other children’s backgrounds, but it was clear that I didn’t belong, and my occasional supper trips to the hotel only served to highlight my feelings of exclusion.

We were expected to do chores, but we had enough to eat and the adults, although strict, were not unkind. There is no comparison with my brief experience in a children’s home in the 1960s and the ugly and painful lives led by many Heim and Verdingkinder. I can, however, identify, if only on a very small scale, with what all of them describe as feelings of abandonment, despair and a sense of powerlessness. The Helios, I subsequently discovered, was owned by Herr Bruendler, a card-carrying member of the Swiss Nazi Party.

Today, Switzerland has one of the highest per capita incomes in the world. One hundred years ago, however, the country was extremely poor. Before World War Two, agriculture was unmechanized and farmers needed cheap labour.

The worldwide economic crisis of the 1930s affected much of Swiss society and created a cycle of real poverty, or a constant fear of it. Sudden illness, an accident or the death of a parent could quickly disturb the fragile balance of a family already living in constrained financial circumstances. The authorities were swift to intervene, sending very young children to homes and orphanages and older ones into servitude.

The Swiss government promoted the idea that hard work, self-discipline and fresh air were a natural corrective for these potentially wayward children and would provide them with the means to support themselves as adults. Farmers worked the children hard: many former Verdingkinder describe getting up before daybreak to help in the barn and carry milk pails to the dairy before school; girls as young as six were expected to cook, clean and knit.

These children and thousands like them were taken from their families without warning. They didn’t know where they were going, nor for how long. Often they were moved to farms in different cantons, and lost touch with their parents and siblings.

I wonder whether this is what happened to Alfred, Maria, Johann, Lina and Anna, the five lost Gilomen siblings?.

I mentioned my research into the Verdingkinder to my friend Brigitte and she told me the following story about her own family. Her father, Hermann Hellmueller was the youngest of eighteen children, and, for reasons unknown, he was allowed to grow up with his parents. His seventeen siblings were all verdingt. Every Sunday, Hermann and his mother, Dora would walk to the neighbouring farms to visit those children who had been placed locally. In her later years, Dora’s adult sons and daughters would, in turn, visit their mother at her home in Willisau, Canton Solothurn.

When Brigitte was seventeen years old, her own mother died of cancer. Within days, the authorities arrived to take her fourteen-year-old sister into care. A kindly neighbour insisted she would help with cooking and caring for the girls and this generous intervention saved Hermann’s younger daughter from servitude on a farm. The year was 1978.

In early 2016 I came across netzwerk-verdingt 3, an organisation founded by former Heim (Home) and Verdingkinder. They gather once a month at the Kaefigturm (Jail Tower) in Bern. Walter Zwahlen, the spokesman for the group, kindly invited me to attend one of their meetings. A few months later, on a cold afternoon in March, I arrived at the Jail Tower. I felt a little apprehensive, concerned that my presence might appear intrusive, but I was immediately made to feel welcome. I joined a small group standing around the coffee urn and soon fell into conversation with David and Heinz, both tall, imposing men in their late 70s.

David Gogniat 4 was born in Bern in 1939, the eldest of four children. His mother worked as a housecleaner. We had very little money but it was a happy childhood, he recalled. When his father left the family, the state intervened and all four children were assigned a legal guardian.

When David was nine years old, his three siblings were sent to a foster family near Gstaad, 100 kilometres from Bern. A year later, in April 1949, two police officers came to the house with instructions to remove David from his mother’s care. Mrs. Gogniat, a physically strong woman, was filled with rage and grief at the thought of losing her son and she pushed the two men down the stairs.

The following day three policemen came to the door and David was taken away and verdingt to a childless farmer and his wife. His day began at 5am and he worked on the farm until 9pm. Attending school was only an option during the winter months. The ten-year old slept in an unheated room in the attic and his foster father beat him regularly, threatening to send him to an institution if he ever tried to defend himself. Once a year, an employee from the youth welfare office came to visit.

As the family didn’t have a telephone, a neighbour would hang a sheet in the yard to warn the farmer and his wife that Frau Madoerin was on her way. On that one day each year, David didn’t have to work and he sat at the kitchen table with the farmer and his wife and enjoyed a good meal. He was given nice clothes to wear and temporarily installed in a bedroom that was not his own. He was never left alone with Frau Madoerin and was never asked about his experiences.

Mrs. Gogniat remained in Bern. From her meagre salary, she was required to pay board and lodging money for David and his three siblings. When, after her death, I was given access to my files, I discovered that my mother had fought like a lioness for us. I will always be grateful to her for that, he said.

When he left school, David expressed a wish to apprentice as a mechanic but was told that there was no money available. He was given three options: chimney sweep, farmer or gardener. He chose farming. Some years later, he got his truck driver’s license and spent many years driving long hauls through Europe and the Middle East. Today, David Gogniat owns a successful trucking business and is a former president of the Swiss Hauliers Association. I find it difficult to show love for my family, he admitted. I can sometimes be very harsh with them. Unfortunately, I was never taught another way.

Heinz Egger 5 was born in 1934, the fourth of six children, all of whom were taken into care. He has never discovered the reason why he and his five siblings were taken away from their parents. Heinz spent the first year of his life, lying, largely unattended, in a narrow cot in an orphanage. To this day, I can’t fully stretch out my elbows, he said. The next six years of his life were happy ones. He was fostered by a childless couple in Wiedlisbach, Canton Bern who treated him as if he were their own. They wanted to adopt him but his birth father refused to sign the papers. In 1939, at the outbreak of WWII, Heinz’ foster father was drafted into the Army and sent to the Swiss border.

When Heinz was seven years old, an anonymous allegation was made against him and he was sentenced to five years ‘re-education’ in the Landorf Boys’ Home near Bern. Walter Zwahlen of netzwerk-verdingt has confirmed that it was not uncommon for Heim and Verdingkinder to be falsely accused (the cases were rarely investigated), as a way of removing them from the community. After being released from the Boys’ Home, Heinz was verdingt to a farmer. Although his work days were long, he always found time to study. He was grateful too that he was, once again, living near his much-loved foster parents.

At sixteen, like David Gogniat, Heinz Egger was told that an apprenticeship with an auto mechanic was not possible. His guardian showed no interest in helping him find a placement. On his own initiative and because he was clearly bright, he was eventually accepted as an apprentice to a metal worker in Solothurn. He returned to live with his foster parents. It was a long journey to work every day. I had to walk 8km down the mountain and then cycle 14km. But I grew fit, an advantage for someone in my profession. In the spring of 1954, I was awarded my diploma and achieved the highest mark in Canton Solothurn.

Heinz continued to work hard, attempting to balance his further education with promising career opportunities and an ever-growing family. He, his wife, Ella and their four children re-located many times. Sadly, however, their marriage did not survive. Eventually Heinz was able to start his own business which he ran successfully well into his retirement. Today he lives happily with his partner, Margrit. As he wrote to me in an email: I have pretty much overcome my difficult childhood and no longer feel overly burdened by it. In the Landorf Boys’ Home I learnt how to be patient, resilient, how to share and help others. Today I am content with my life.

Heinz Egger

The people I met that day at the Jail Tower in Bern are able to speak of their painful childhoods, but there are thousands in Switzerland who have been completely broken by their experiences; some are literally speechless; others have taken their own lives. The stigma was so great that many never told their partners and children that they had been verdingt.

One woman I spoke to told me that she had been fired from her job as a secretary when it was discovered that she was a former verding child. We were good enough to clean the toilets but not to work in an office, she said bitterly. Women generally suffered more than men as it was assumed they would get married and therefore didn’t need to learn a trade.

As adults, many former Verdingkinder chose careers that provided them with freedom and independence. Like David, Charles Probst, known as Scharli, found work as a long-distance truck driver, which enabled him to travel extensively, all expenses paid. He told me about his experiences in Iran, delivering aircraft hangars for their fighter jets. When the Iran-Iraq War broke out, he spent fifty days stranded in the desert with a colony of foreign truck drivers. I was struck both by Scharli’s resourcefulness and by his modesty. He was, I subsequently discovered, not just a truck driver but, like David Gogniat, the owner of a successful transport company.

Scharli later told me that his two younger brothers had been sent to the Kinderheim Helios on the recommendation of the village doctor in Adelboden and Bern social services. Their mother, herself a Verdingkind, was working as a maid when she became pregnant. She was immediately dismissed, even though the baby’s father was the farmer’s son. Scharli grew up on a farm near Bern and when, at the age of ten, he discovered that the people he lived with were not his biological family, he tried to take his own life. He put the barrel of a rifle into his mouth but as he reached down, the bullet fired, grazed his guiding finger at the muzzle and went through the roof of the barn.

I think of my grandmother and I wonder whether she knew, as she was growing up, that she had not one, but six half-siblings. Did her father ever talk about his missing children and why they’d gone away?

Many former Verdingkinder say they could have endured the back-breaking work, the under-nourishment, even the violence, but they were never able to reconcile themselves to the absence of kindness and affection. As children they were not precious to the adults around them.

Moments of tenderness were rare and many sought warmth and comfort from the animals on the farm. Without good role models or mothers to explain the changes of adolescence, girls married young or gave birth to children outside marriage, perpetuating the legacy of social exclusion. Sexual abuse was not uncommon, and pregnant girls would vanish in the night to another farm in another canton, where the baby would be given up to a children’s home.

The need to survive their physical and emotional circumstances suffocated a natural ability for intimacy and the divorce rate amongst former Verdingkinder is high. In the last ten years, those who have been given access to their records often discover that important information has been omitted or falsified. In some cases, the files have been destroyed altogether, which they experience as a double betrayal.

If my grandmother’s half-siblings were verdingt, then it seems likely that the same fate befell members of my grandfather’s family. Rudolf, my paternal great-grandfather and his first wife, Magdalena, were married for twelve years. In 1884, she died and at the age of thirty-six, he found himself with fourteen children to support. Shortly afterwards, he married the widowed, childless Maria. Second wives recognised their value and often chose to negotiate the number of stepchildren they were prepared to accept in the marriage. The rest were verdingt. When she was forty, Maria gave birth to my grandfather, Ernst.

Ernst’s two half-sisters, Elise and Bertha, had emigrated to the American Midwest in 1895 and, following Rudolf’s death and Maria’s third marriage to Otto Zingg, Elise wrote suggesting that Ernst join them in America. Maria felt that her son was too young to make the long journey alone. My mother always claimed that the departure of her father’s two favourite half-sisters and his mother’s refusal to allow him to go America were losses from which he never fully recovered. She even went so far as to suggest that they were factors which contributed to his suicide in 1943.

Elise and Bertha Kummer were eight and ten years old when their mother died. Neither of them spoke very much about their early lives in Switzerland but it seems likely that they were verdingt. In 1895, the two young women sailed from Rotterdam to New York where they boarded a train to Chicago and on to Wisconsin. For most emigrants, leaving their homeland was not a choice but a necessity, driven by hunger and poverty.

Four years after arriving in the Midwest, Elise married the German-born Carl Fritz and they moved to Madison. Carl was a carpenter and in 1901 he founded the Fritz Construction Company which went on to build some of the city’s best known public buildings, including the First National Bank, the Kennedy Dairy Company and the private home of Glenn Frank, president of the University of Wisconsin.

In 1932 President Hoover invited Mr Fritz to the White House where he was honoured for his work. Elise christened their first born Fidelia Helvetia, ‘Faithful Switzerland’ and spoke Swiss German to her as she was growing up. Perhaps Elise, aware that her little brother Ernst was at risk of being verdingt, wished to provide him with a home and a future. She could offer him a good life in America, growing up alongside his little niece, Fidelia and learning a trade at the Fritz Construction Company.

He would also have been a link to all that she had left behind and someone to whom she could speak in her native language. In spite of her great wealth, Elise never returned to visit her homeland. Her sister, Bertha did not marry and moved to New Glarus, Wisconsin, the archetypal Swiss town, full of chalets and umlauts, yodel music and pork products.

My grandfather, like his father before him, was a policeman. Part of his job would have been to forcibly remove children from their homes, their siblings, their identities, their childhoods and, above all, their mothers. The Swiss authorities considered that poverty was socially inherited, and believed that removing children from their impecunious circumstances would guarantee greater social and economic productivity in ensuing generations. This policy came at a terrible price for thousands of children and their families as well as for the soul of Switzerland.

In 2013, the Swiss government offered an official apology to all former Heim and Verdingkinder 6. A few years later, an initiative was launched seeking financial reparation for the surviving victims, together with a comprehensive investigation into the history of Switzerland’s indentured children. Scharli Probst was active in helping those who qualified for the money but couldn’t navigate the forms. Many former Verdingkinder were poorly schooled and struggled to read and write. Others remain wary of the authorities and fear that their personal information could be used against them.

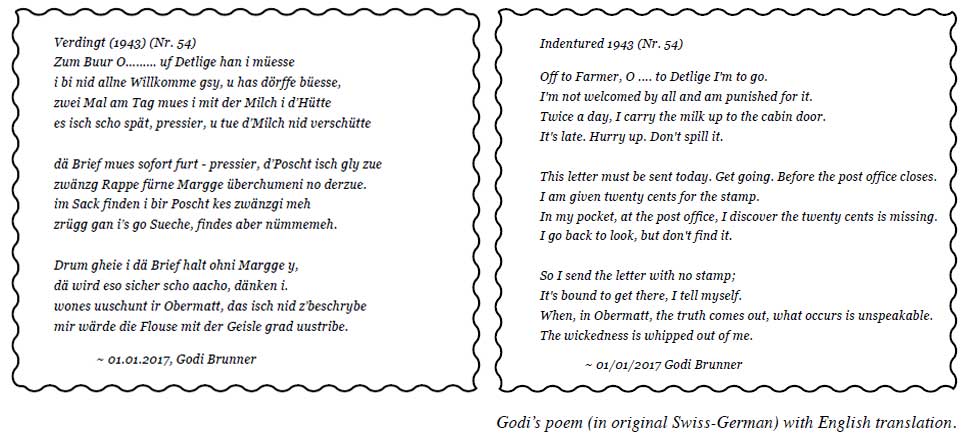

Godi Brunner age 14

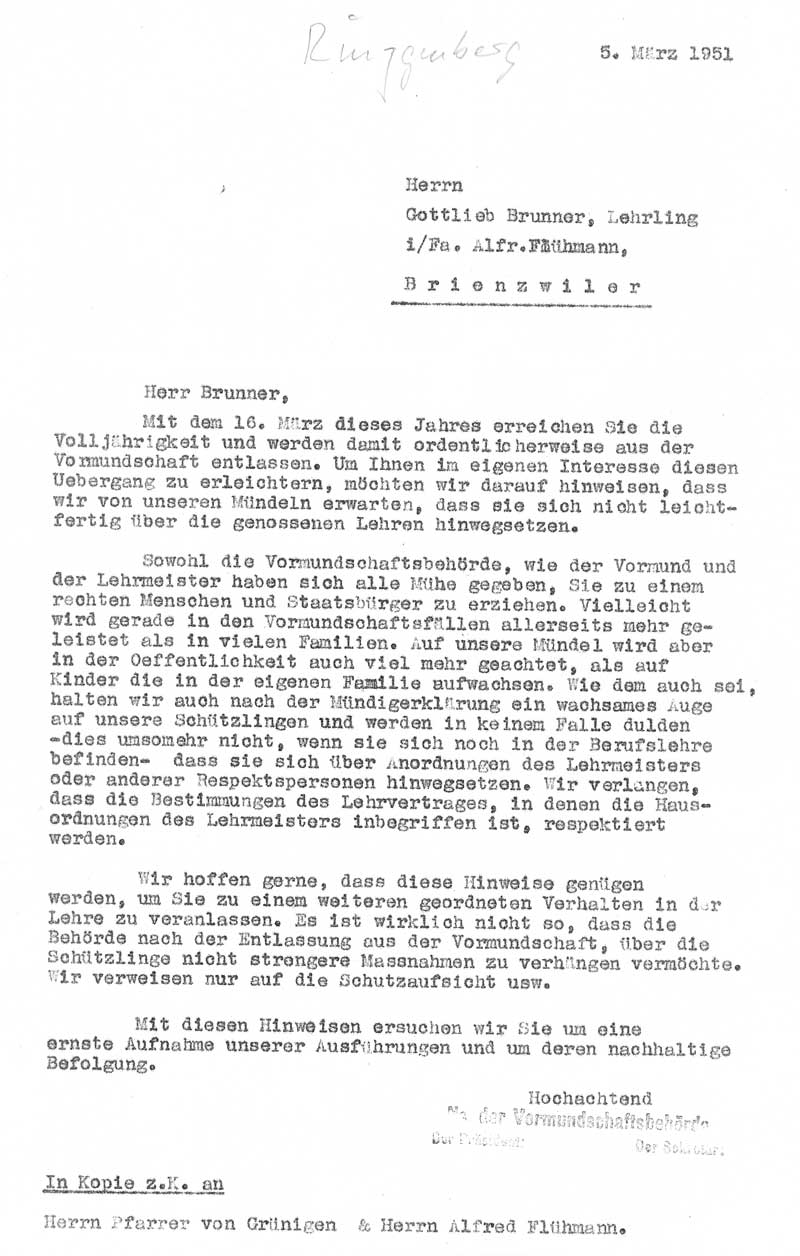

In the spring of 2016, I visited the Stolen Childhood – Verdingkinder Speak exhibition at the Ballenberg Museum near Bern where Gottlieb Brunner had offered to be my guide. Godi has a freckled face and warm, sad eyes and, like many former Verdingkinder, he is strong but suffers from spinal injuries incurred during childhood when he was made to carry heavy weights up and down mountainsides.

Godi was verdingt to a farmer when he was eleven years old. In spite of the fact that his grandparents lived in the same village, he was forbidden from visiting them. His grandfather was a skinner by trade and his job included the burying of animal carcasses. He would cut away the un-spoilt meat and take it home to feed his large family. Some of his 18 children died of the Spanish flu. Others succumbed to typhoid.

Godi Brunner’s Grandfather

At the age of fifteen Godi was committed to the Waldau Psychiatric Clinic in Bern where he spent a year undergoing electric shock treatment for enuresis. Many years later, David Gogniat’s mother was also sent to the Waldau, following a diagnosis of religious mania.

David was able to secure his mother’s release on condition that he agreed to take full responsibility for her. During my own family research in 2016, I discovered that the so-called ‘care home’ where my maternal grandmother spent the last seven years of her life was in fact the Waldau Psychiatric Clinic.

Rosa, like Mrs. Gogniat, had a strong faith in God although there is nothing maniacal about her letters to my mother in England. They simply offer loving support in a time of personal crisis. As recently as 2017, an article in a Bern newspaper 7 described disturbing practices at the Waldau with regard to isolation and restraint procedures.

A commission subsequently ruled that patients should not, in future, be handcuffed or placed in solitary confinement for longer than a prescribed period of time.

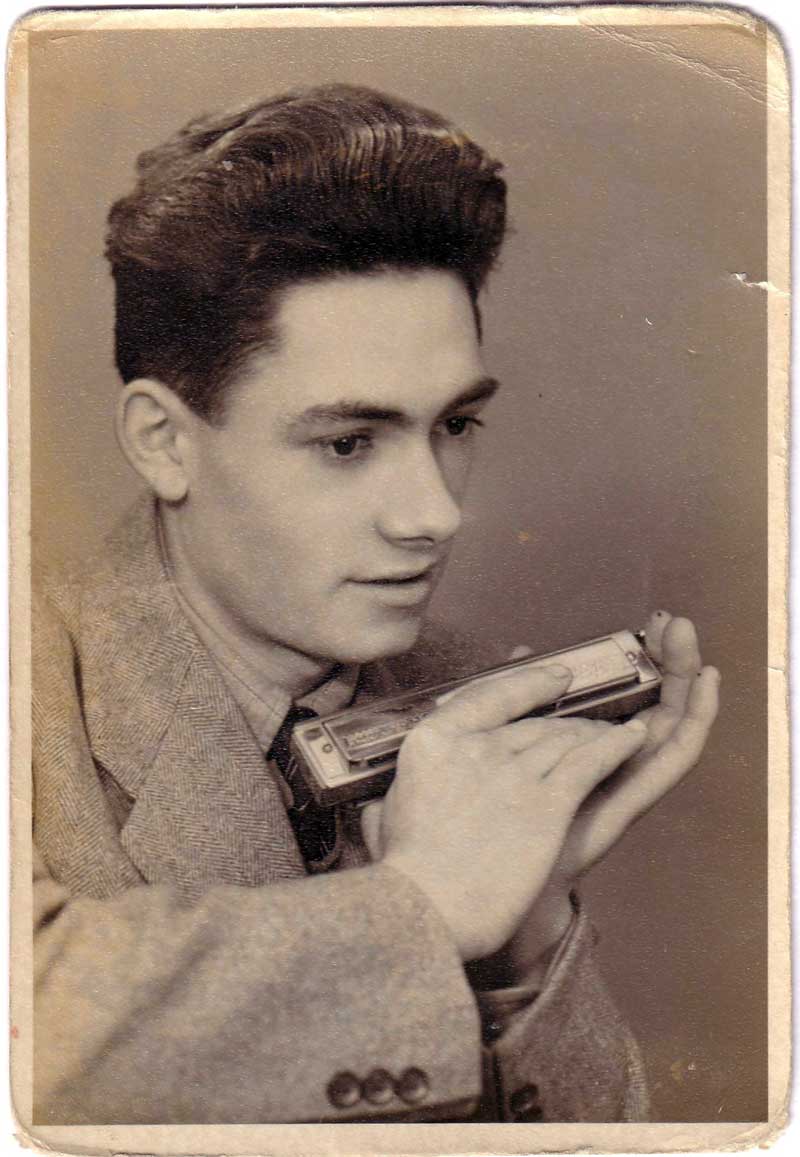

On March 16th 1951, on the occasion of his twentieth birthday, Godi Brunner received a letter from the authorities, informing him that his guardianship was at an end. He was warned, however, that a close eye would be kept on him. It was explained that this was not a threat but a form of ongoing protection. A copy of the letter was sent to the local priest.

Godi aged 20

Godi Brunner’s release from guardianship at age 20. This is a copy of the original letter in German dated March 1951.

Translation of the letter:

Mr. Brunner,

On March 16th of this year you will be of legal age and thus be released from your guardianship. For your own benefit and in order to facilitate this transition, we trust that you will not invalidate the advantages you have been given.

The authorities, your guardian and your apprenticeship master have all worked hard to raise you into an upstanding human being and a good citizen. It is possible that, in these guardianship cases, more is offered and provided for the child than in many families. Once in the public eye, our charges are more highly regarded than children who have grown up in their own families. Be that as it may, a watchful eye is kept on all our protégés and we will not tolerate any disobedience, either towards your apprentice master or indeed towards anyone in a position of authority. We demand that the rules of your apprenticeship are respected.

We hope that these recommendations will be sufficient for you to maintain orderly behaviour. It is certainly the case that the authorities, following the release of their charges, have no wish to impose strict measures. We advise you only in terms of our role as protective supervisors etcetera.

We encourage you to seriously follow our guidelines and to maintain strict adherence to them.

Yours sincerely,

Your Guardian

The authorities were true to their word. In his early twenties, Godi began dating Gertrud, a young widow with two small children. Within three months he was summoned to an interview with social services, where a panel of four administrators informed him that, unless he married this young woman, both she and her children would be sent to institutions. Reluctantly, he agreed.

In spite of the appalling abuse Godi experienced, both as a child and later as an adult, his determination enabled him to gain professional qualifications and sufficient savings to start his own painting and decorating firm. He is an accomplished artist, poet and wood-carver and a man of great sweetness and integrity.

When our granddaughter was born in 2020, Godi gifted her a hand-carved Swiss chalet. It has a cedar-shake roof, red shutters, window boxes full of flowers, a neatly-stacked woodpile with its own tiny axe and a water pump.

The chalet also doubles as a money box. Godi told me that he had inserted a flap behind the slot so that any deposited coins could not be retrieved by searching fingers. Thriftiness is a quality that many former Verdingkinder share.

Financial independence provides greater freedom of choice and self-determination, something very few of them experienced as they were growing up. Thea’s chalet bank sits on the shelf of her nursery, as yet empty of coins, but overflowing with the generosity of a man she may never meet.

In the winter of 2017, I went back to Bern to see Scharli and together we visited an exhibition at the Jail Tower titled Verdingkinder – Portraits by Peter Klaunzer 8.

The idea behind the project was to pay homage not only to the twenty-five men and women whose photographs shaped the exhibition, but also to dignify the hundreds and thousands of former Heim and Verdingkinder who have died in recent years.

The sentence that accompanied Charles Probst’s picture was: I wanted to kill myself and I asked Scharli what, as an adult, had kept him from making another attempt on his life. He replied that having been told he was worthless and would never amount to anything, he was determined to prove people wrong.

He had always relied on himself, trusted only himself and never depended on others to provide him with anything, least of all a sense of his own worth.

Scharli Probst standing outside the Peter Klaunzer exhibition in Bern. His face was used on the advertising posters.

In Switzerland every cow is tagged and registered, but to this day, no one knows for sure how many children were removed from their families. Scharli explained that what is important to him is not the compensation money.

His hope is that stories of the Verdingkinder will be recorded in the history books to be read by future generations of Swiss schoolchildren because, as he pointed out, the money will soon be gone, as will the school groups passing through the exhibition.

In March 2023 I spoke to Marlene Brown who was born in Biel, Canton Bern in 1935 and emigrated to Campbell, California in 1956. Her story echoes many others I have heard. Marlene’s mother died when she was seven years old and she was placed with foster parents who were physically and psychologically abusive.

Her eleven year-old brother was verdingt to a farmer. Until she was nine, Marlene was under the impression that both her father and her brother were dead. I made my own little box to live in she told me. It was a way of dissociating from her surroundings and protecting herself from the outside world. Later she went to live with her father and his new family. She found work in a silk factory but was forced to hand over all the money she earned to her stepmother.

Marlene met her future husband, a soldier in the US Army, at a Zurich bus station. She and Lyn Brown fell in love and in 1956 she left Switzerland to begin a new life in California. In the 1980s the Browns moved to Ohio.

Like many former Verdingkinder, Marlene never spoke to anyone about her painful childhood. I didn’t see the point of dragging everybody into my story. It didn’t seem useful, she said. In the early 2000s, however, when survivors’ stories began surfacing in the Swiss media, Marlene began to wonder. This happened to me and my brother too. We were separated from our father and from each other and were sent away.

In April 2013, Simonetta Sommaruga offered a public apology, on behalf of the federal government, for the shameful practices which had continued, in some form or another, until 1981. Marlene wrote to Sommaruga and the Justice Minister wrote back.

With the help and support of the Cincinnati Library, Marlene wrote a book about her life as a Verdingkind 9 She received a check from the Swiss federal government for twenty-five thousand francs which she has invested on behalf of her grandchildren. I don’t need it now, she said. My husband Lyn and I were frugal, we saved money and we travelled a lot. We loved hiking and kayaking. I had a good life and a happy marriage.

In the same year that Sommaruga made a public apology, the Swiss philanthropist, Guido Fluri, himself a former Boys’ Home resident, financed a museum in Muemliswil, Canton Solothurn, dedicated to all former Heim and Verdingkinder .

In 2016, Fluri launched the initiative which proposed financial compensation for victims of the state’s forced child labour policies. Resistance came from the Swiss Farmers’ Union which feared that its members might subsequently be held to account. Fluri, however, was less interested in blame and retribution than he was in finding a good solution for the victims. We had to be quick, because many of them were already old and frail he explained 10.

In February 2019 Guido Fluri and two Swiss victims of clerical abuse were invited to a private audience with the Pope in Rome. Francis apologised to them as individuals and to all the Swiss victims they represented. He asked for forgiveness from ‘the bottom of his heart’, Fluri later told the Swiss Catholic press agency 11

Scharli’s final wish has also been fulfilled. In 2017, Professor Hansueli Grunder from the University of Basel, together with Walter Zwahlen and the Carl Albert Loosli Foundation12 created a course for schools with the intention of educating children and promoting discussion on the subject of Switzerland’s shame: the legacy of the Heim and Verdingkinder.

I end with a poem by Marlene Brown

Forgotten Children

Two young children all alone

no one to love them,

no one home.

The boy was eleven, his sister still small,

he was her hero,

he seemed eleven feet tall.

Gone was her mother,

father and brother

she was alone,

there was no other

She didn’t know why her mother died,

that she would never again be by her side.

Why did our father give us away?

We were not bad kids,

so why couldn’t we stay?

Abandoned by all, even by God above,

Where was compassion?

Where was the love?

Darkness begins, her heart turns to stone,

where was her family?

Why, was she even born?

Sent into foster care with total strangers,

soon she discovered she was in danger.

Hunger and beatings prevailed through the day,

how much longer in this hell

did she have to stay?

Into another foster home she went,

no hugs, or love were ever given,

but she was content.

Many hard and lonely years passed by,

her father suddenly took her home,

she did not ask why.

Good and bad days would come and go,

as each day went by so very slow.

Her age of twenty did finally arrive,

after all these years she felt unburdened,

free and alive.

A handsome young man took her far away,

where she felt happy,

so she decided to stay.

Husband and wife they became long ago,

it is now fine with us both,

if life goes by slow.

Marlene Brown-Bieler, 2010

In memory of Charles ‘Scharli’ Probst 28th April, 1930 – 8th October 2022

Swiss American Historical Society Review, June 2023

Brigham Young University

https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs review/vol59/iss2/2/

Excerpts from The Absent Prince: In search of missing men by Una Suseli O’Connell

The Conrad Press, 2020.

1 Frances Stonor Saunders, The Vanishing, (The Guardian Weekend, April 15th, 2000)

2 Marco Leuenberger, Loretta Seglias (Hrsg.) Versorgt und vergessen. Ehemalige Verdingkinder erzaehlen. Rotpunktverlag, Zuerich 2008

3 https://www.netzwerk-verdingt.ch

4 Sandra Rutschi Was ehemalige Verdingkinder in ihren Akten finden (What former indentured children discover in their files) Tages Anzeiger, Bern August 4th, 2014.

5 Heinz Egger Personal Recollections shared with the author.

6 Swiss minister apologizes to victims of forced welfare. https://www.reuters.com

7 Marius Aschwanden, Kritik an der Waldau, Berner Zeitung, August 30th, 2017

8 Verdingkinder/Enfants Places, Portraits von/de Peter Klaunzer: A photographic exhibition by Keystone and the Polit-Forum Kaefigturm (Jail Tower) together with netzwerk-verdingt. Photographs and accompanying book in German and French.

9 Marlene Brown-Bieler, Verdingkinder, the Indentured Children: The life story of one of

the children. marblyn@gmail.com

10 Susanne Sugimoto, Guido Fluri – in the thick of it. The Philanthropist.ch 31st August, 2022

11 Christa Pongratz-Lippitt, Francis promises abusers will be handed over to secular courts, The Tablet, March 5th, 2019

12 https://www.carl-albert-loosli.ch