Educated Americans are the most charming and vital people I know.

Peter O’Connell, diary entry, May 1949

Peter O’Connell and Alan Pifer met as students at Cambridge in 1946. Peter was from London and Alan from Massachusetts.

Pifer had attended Groton School and graduated from Harvard. By 1950 he was Director of the Fulbright Commission in London.

Alan knew that Peter was interested in working in America and offered to write to Jack Crocker, the Headmaster at Groton, recommending his friend for a teaching position at the school.

In January, 1951, Peter mailed his letter of application to Reverend Crocker. He was surprisingly frank about his emotional difficulties: I mention these because I know Groton has high standards and I don’t want to risk letting you down.

Four days later, my father received a letter from America, inviting him to Groton to teach English.

Later the same month he met Robert Moss, the school’s Divinity master, in London. In his diary, Peter writes: Moss sank three large gins and smoked a great deal. A good sign that Groton isn’t too stuffy in its religion.

His Fulbright travel grant came through, the US Embassy provided him with a work visa and the hospital signed him off as tuberculosis free.

Peter bought a one-way ticket on the QEII and set sail for America on September 5th, 1951.

The city customs official in New York was a tad suspicious of the Anglo-Irishman with his one bargain suitcase of personal effects and five tea chests of books. He insisted, therefore, on prizing them open, one by one. By the time he reached the third chest, he had taken rather a liking to my father and decided that his story about the books was probably true: OK, Peter, we’re done. Welcome to America. Now get outta here ….

Peter fell in love, right there and then: Where else, but in the United States, would a government official call you Peter?.

He spent a few days with Alan Pifer’s parents in Shirley, Massachusetts and then made the journey to Groton School, where he was greeted on the steps of Hundred House by the Reverend Jack Crocker.

The two greatest forces in America are Niagara Falls and Endicott Peabody

Old Groton legend

Groton School was founded in 1884 by the Reverend Endicott Peabody.

Peabody was educated at Cheltenham School and Trinity College, Cambridge and he modelled Groton on the public schools of England.

He studied theology and in 1882 was sent on pastoral assignment to Tombstone, a town which, three months earlier, had witnessed the gunfight at the OK Corral. The young seminarian was not shy about entering the saloons and asking for donations from poker games and it is said that Wyatt Earp contributed a pew to Endicott’s new Episcopal church.

Groton and Peabody were synonymous and the school was created in his image.

Former alumnus and President of the United States, Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared that apart from his parents, Endicott Peabody was the strongest influence in his life.

Peter loved Groton from the moment he arrived and was struck by the lack of inflated egotism amongst the boys: Nor is there much snobbery, though quite a few families appear to be descended from American presidents. At supper last night I spoke to three boys, all of whom were direct descendents of Coolidge, Taft and Roosevelt.

There is tradition at Groton that when a new President takes office, he is invited to write a letter to the school, offering words of wisdom and encouragement to the students. In 1962 President Kennedy wrote: There was a period when it seemed as though a Groton graduate might be President more or less permanently. I am sorry that the best I have been able to do is make a Grotonian Secretary of the Treasury.

In 1970, President Nixon got the wrong end of the stick and sent a signed photograph, saying how flattered he was by Headmaster Wright’s request. President Obama’s letter encourages Groton students to dedicate their energy and talents to their classrooms and communities.

Reverend Peabody considered Groton to be an extension of the family. Meals were taken at tables with a master and his wife and there were Bible readings and prayers before bed.

When Reverend Crocker succeeded Reverend Peabody in 1940, he reinforced the adviser system, which made individual masters accountable for the academic and social progress of the boys. In his first year at Groton, two of Peter’s advisees were the sons of eminent theologians – Reinhold Niebuhr, whom President Obama has described as his favorite philosopher and Walter H. Gray, the Bishop of Connecticut.

Groton School by Harding Mudge Bush

Groton School lies thirty five miles west of Boston, with views across the Nashua River valley and the mountains of Wachusett. The campus is arranged in a circle and Schoolhouse, with its white columns and gold cupola, faces Hundred House and its Palladian windows. Peter writes:

What a beautiful place this is. The buildings, the setting, the interiors, everything is lavish and tasteful. My small dorm and my flat are attractive and very comfortable. I have a big open fireplace in the sitting room and a telephone. Many of the staff have been to Oxford or Cambridge, the chapel is modelled on Magdalen, there is a full peal of bells in the tower and the complete volumes of Punch in the Library.

Peter considered the boys to be polite and interested, although not as academically advanced as the pupils he had taught at Highfield School in England. He appreciated the religious life at Groton and found both Morning Chapel and House Prayers to be friendly and relaxed:

Sunday Chapel is more formal and the choir wear red cassocks, but aesthetically, it is a very happy experience with the organ, bell and voice music. The religious meaning remains elusive yet I respect the religious life at Groton in a way I did not at Highfield.

One of Mr. O’Connell’s responsibilities was to act as assistant coach to the soccer team. He was relieved to discover that the standard was so low he could almost pose as an expert. In spite of a weak understanding of the rules, the squad showed tremendous enthusiasm: they’re dead keen and go flat out, never grumbling or being silly.

He began an active campaign on behalf of soccer, fighting to raise its status in the school and encouraging more spectators to attend practice games. At the end of the season, Peter was presented with a small silver football engraved with the words: PO’C Coach GS 1951.

The following season, a newly arrived first former approached Peter and asked whether the rumour he had heard was true, namely that Mr. O’Connell had once been invited to play for a professional soccer team in England How the Highfield folk would have laughed at that!

In the classroom, Peter sought original ways of engaging the boys’ interest. Horrified to discover how little his 6th Formers knew about Shakespeare, he kick started them with Hamlet, inviting their opinions of the Prince of Denmark, then, confusing them by criticizing Hamlet and defending Polonius.

He gave them the task of summarizing the play and then rewriting it in the Shavian idiom: transposing Shaw into the 16th century and making him revolutionary, didactic and progressive but in an entirely different context. He asked them to write a new version of the first soliloquy by Shawspeare. I hope to have more fun with Shakeshaw tomorrow.

The boys’ views were certainly provoked and there was much lively discussion in Mr. O’Connell’s English class.

Peter was much loved at Groton. He was an intelligent and thoughtful companion and soon became a regular at the supper tables of faculty families. Gina Murray and Edie Hardcastle enjoyed his mildly flirtatious manner and Peter successfully avoided offending their husbands by openly complimenting Jack and Fitz on the loveliness of their wives.

The Hardcastle Family

He was a favourite with the children too and little Phoebe Bowditch, out in the vegetable patch with Peter one day, declared: ‘We invite you to dinner, Peter, because we love you’. He attended birthday parties and school plays and when he was away from Groton, he sent the children postcards.

When Peter wasn’t being wined and dined by the Murrays, the Bowditches and the Peabodys, he was at the ‘Bull Run’ with Corky Nichols and Jim Hawkes, enjoying a duckling and ice cream supper: what a contrast with the shabby old Highfield sitting room and tea at nine o’clock from cracked cups out of a metal teapot.

He spent Thanksgiving with the Pifers where he went horseback riding and tasted his first pumpkin pie. In December, a visiting Headmaster from Texas, offered him a position teaching History at a school in Dallas and within the week, Jack Crocker had invited Peter to his study and guaranteed him a position for the following academic year. He was doing a fine job, Jack declared. Everybody said so.

In the week before Christmas, Peter joined Norris Getty and Jack Murray on a trip to New York. They shared a room at The Paramount Hotel on Times Square and while his colleagues attended a teachers’ convention, Peter explored the city and its bookshops. It was Norris and Jack who took Peter to see his first musical: Mary Martin in ‘South Pacific’.

He spent Christmas with the Pifers and then caught the train to Far Hills, New Jersey where he had been invited to stay with Groton parents, Hughie and Cocky Hyde. He went pond skating and danced with an array of beautiful women at a party given by Henry Ford’s brother-in-law: They are decent folk, of good incomes, the men unassuming and straight-forward. There was no buffoon or elegant poseur present as at similar gatherings in England.

On New Year’s Eve he attended the Hunt Club Ball, founded by Hughie’s grandfather, where he danced with a cousin to the future Queen of England. It was a glamorous life and my father was enchanted by it.

In March of 1952, Peter proposed the introduction of a literary society at Groton as a way of encouraging boys to read for enjoyment. At each meeting, a student would deliver a paper on a subject of his choice. There was general astonishment at O’Connell’s idea and very little enthusiasm from the faculty. Undeterred, he raised the subject again and Jack Crocker decided to authorise it on a trial basis.

Peter O’Connell (centre) on the Circle at Groton

A group of six senior boys gathered for an informal meeting in Mr. O’Connell’s study and fifty turned up to the second meeting, listening with dead-pan or small smiling expressions. After my impassioned harangue not a soul spoke or had questions to ask.

Jim Amory delivered the first paper on the subject of the harpsichord, marred only by too many ‘ums. Jim later went to Mr. O’Connell’s study for tea, where he complained about the general lack of enthusiasm amongst the faculty. Peter defended his colleagues but was secretly pleased that his newly formed society had launched so successfully.

In March of 2017, Jim Amory, now in his late seventies, wrote in an email: I bet Mr. O’Connell made a hell of a schoolmaster. He was a man with passions, and he wasn’t afraid to express them.

Peter began to attend Groton’s Drama and Debating society meetings but found the tone overly earnest and the material too factual. He also went along to Jim Hawkes’ play rehearsals and offered much unsolicited advice I told Jim I thought the boys were poor – bad speech, lack of imaginative insight, no inspiration.

Surprisingly perhaps, Hawkes was not offended and invited further suggestions: I succeeded in diagnosing some of the main complaints. Peter Nitze intones on final consonants and turns simple vowel sounds into dipthongs. I also got the boys to laugh. The tavern scenes are going to be dull without laughter.

In March 2017, Edward Gammons, cast in the role of Falstaff in Groton’s 1952 production of ‘Henry IV’ wrote:

Mr. Hawkes gave me over into the care of Mr. O’Connell. For weeks we went over every line that Falstaff spoke, every gesture. We talked much about Elizabethan theatre. This led to other discussions about English history, heroes and literature. My passions for Shakespeare, Elizabethan drama/literature and for the theater in general can be, at least in part, traced to Peter O’Connell. It is one of the happiest memories of my Groton education.

Tom McNealy, a good looking lad from Chicago, has taken me under his wing and is very charming in his efforts to make life easier for me.

Peter, diary entry, 1952

In the summer of 1952, my father was invited to stay with the McNealys at their home on the shores of Lake Michigan.

In 2000, Tom McNealy wrote to my father in England.

There must be some truth to the fact that we never forget important people in our life. You were the best and nearly fifty years later, I still cherish our year of learning and our days of challenges. You are so important to me in my order of things. I thank you for being in my life.

He enclosed a faded photograph of Peter taken on the campus at Groton. It was, he wrote, one of his most treasured possessions and had lived on the door of his fridge for more than forty years. I wrote back and told Tom that Peter had died in 1998. I made a copy of the photograph and returned the original to him.

Thomas McNealy died three years later in 2003 at the age of sixty nine.

By the start of the summer term, however, Peter was struggling once again I feel tired and dispirited and am conscious of intense spiritual loneliness.

It was in his relationship with the boys that Peter felt most alive, perhaps because what he felt for them was instinctive and uncomplicated. In spite of its academic brilliance and attention to morality and manners, Groton School remained, by its very nature, a holding pen for the sons of wealthy and eminent men. The Groton Boy had no regular contact with his father and little opportunity to share with him his scholastic and athletic successes. He was denied the opportunity to learn from, to talk to, or indeed to be angry with his father on a daily basis. Peter knew what father hunger felt like and he had an intuitive capacity to tap into the hearts of those boys who, like him, missed their fathers’ physical and emotional presence.

Peter decided not to return to England that summer but to find a job in America. Jack Crocker offered to write to his friend, Francis ‘Duke’ Sedgwick.

Dear Duke,

This is a long shot but we have a very attractive and able young Englishman teaching here, who is eager to get himself a job this summer. He is a good soccer player, is very adaptable and has an excellent head on his shoulders. He would be prepared either to tutor or take a job on a ranch, or both.

Minty is in good form and Mary joins me in sending you and Alice our love.

Soccer Squad 1953 Image reproduced with kind permission of Groton School

Unfortunately, Mr. Sedgwick had nothing to offer Peter, but, in early June, a letter arrived from William Wood-Prince, whose son, Alain, was a student at Groton. Wood-Prince was President of the Union Stock Yard and Transit Company of Chicago and he offered my father a summer job as a yardsman.

On the Greyhound bus from Boston to Cincinnati, Peter read Upton Sinclair’s ‘The Jungle’, a horrifying account of life and practices in the early Chicago stockyards. It is said that after reading The Jungle, President Theodore Roosevelt stopped eating sausages and began investigations which resulted in the Meat Inspection Act of 1906.

On July 2nd 1952, Peter met ‘Billy’ Wood-Prince and his Vice chairman, Mr. O’Connor from County Kerry who subsequently arranged a three hour tour of the stockyards: a wonderful organisation capable of handling thousands of cattle and hogs a day.

The following morning, Peter punched his card and reported for work at A3 weighing scale.

On his second night in Chicago, my father got very drunk with a Republican politician: We ate and drank so much that I was only semi conscious but remembered Hacker’s bodyguard telling me that Chicago police deal with pickpockets by breaking their fingers. I got Hacker very wild by praising Eisenhower.

The 4th of July was a national holiday and Peter’s arrival in Chicago coincided with the Republican and Democratic nominating conventions for the Presidency.

Today’s proceedings were a mixture of a Cup Final and Bertram Mills’ Circus. There were bands and processions, charabancs and rosettes. Everything that could carry a favour was pressed into service – helicopters, an elephant (which went berserk), banners, flags, buildings. When the full moon rose, I half expected to see ‘I Like Ike’ painted on it.

It’s hard for me to imagine Peter in denims and a cowboy hat, driving cattle in the Chicago Stockyards. My father disliked physical activity because it invariably meant time away from his beloved books. Judging by his diary, however, he worked uncomplainingly as a yardsman for six hot weeks.

17,000 cattle came through today and it all began with a torrential rainstorm. I blessed my plastic suit. Then came the sun and it felt like a Turkish bath. I worked for twelve hours and spent most of the day at the weighing scale, driving the cattle to their pens and then loading them into railroad cars. I was blinded with sweat but it was very satisfying work and I held the vision of a cold bath and a gin sling at the end of my shift. The following day, temperatures fell to 60 degrees extraordinary change – yesterday cattle died of heat, today one calf died of cold.

In a letter to Jack Crocker, he writes:

I came to meet people and see things in this great heartland of America and by Jove I’ve met and seen both. The yards themselves are a great American enterprise but it’s the men who work here that delight me most – they’re as fine a bunch as you’d find in a month of Independence Days – genial, warm-hearted, cheerful (and blasphemous!), always willing to judge tolerantly. I have also met people from every walk of life outside the yards and I’ve been impressed there too with the same kindness and friendly hospitality. The last vestige of formality remaining in ‘Peter’ has disappeared – I’m ‘Pete’ to all in Chicago.

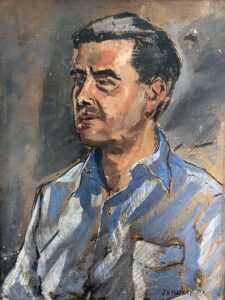

Oil Painting of Peter O’Connell by Jack Murray

I am stunned by this revelation, by the thought that anyone would call my father Pete. No one called him Pete. Not ever.

It is clear that Pete’s position as a yardsman was somewhat unique. I doubt that every new employee was given a three hour tour of the plant on his first day. This was followed by a cocktail party where he met Mrs. Stevenson, the divorced wife of the Governor of Illinois and a dark horse for the presidency. He also received an employee pass which gave him free access to the Convention centre.

Peter attended a reception for Eisenhower, heard many of the nominating speeches and met people from all over the Union. General Eisenhower won the Republican nomination and Richard Nixon was his Vice President.

After the five day party was over, Peter felt flat and dispirited: The light of common day seems very dull. He enjoyed working on the scales and didn’t mind shovelling dung in the terrific heat but he found the weekends lonely and longed for company.

On July 21st, the Democrats arrived in town I enjoyed Eleanor Roosevelt’s speech and Stevenson looks like the man.

During the convention, Peter met a young woman selling raffle tickets who invited him home for tea. Tea in America is an engaging euphemism for hard liquor. After a few dry martinis at Ken and Helen’s Lake Shore Drive apartment, they took their new-found friend to the Raquet Club for dinner, then back home for more ‘tea’.

The Crowells began to include Peter on weekend trips to Kenilworth and pretty soon his social life had regained its bounce. When he wasn’t hanging out with the Crowells and their friends, he was arguing politics with Joe in the Tap Room at the Stock Yard Inn.

The only association I have with Kenilworth, apart from my father’s wealthy Chicago friends, is Walker Evans, the documentary photographer known for his powerful images of rural Alabama during the Great Depression. Evans had lived in Kenilworth as a child.

In 1983, I was staying with Gina Murray at her summer home on Cranberry Island, Maine. Gina’s husband, Jack, taught Art at Groton School until his death in 1969.

At a supper party, I was seated next to Isabelle Storey, the former Swiss wife of Walker Evans. She told me that in the late 1950s, at the age of 25, she had left her husband to marry Walker, who was thirty years her senior.

In fact, I found Isabelle’s stories less interesting than some of the others I heard around the dinner table that night. Cranberry is both beautiful and isolated and during July and August the island is popular with artists. One summer, an island boy fell in love with a girl from the mainland and was angry and heartbroken when she ended the affair and returned to Boston. He was so angry in fact that he drove a bulldozer up to her parents’ house and pushed it over a cliff into the sea.

Jack and Virginia Murray, with Lea O’Connell, 1965

I wonder what went through my grandfather’s mind as he read Peter’s letters telling him of his life in the Chicago suburbs, drinking milk punch with his millionaire friends. I expect he was happy for his son, relieved he’d got away and made such a good life for himself. Henry, Peter’s grandfather had been a cattle farmer in Co. Cavan in Ireland. Had he lived in the rural Mid West, he too would have sent his cows for slaughter to the Union Stockyards. Cattle were in Peter’s blood and the summer he spent in Chicago was perhaps an unconscious bid to reconnect with his severed, but still felt, Irish roots.

As his time in Chicago came to an end, Peter began to spend what he referred to as gentleman’s days in the stockyards, talking to the yardmasters and touring the Grain Exchange. He never visited the killing beds or the packing houses and his journal, surprisingly, makes no mention of the sounds and smells of the Yards – the metallic odour of blood, the squealing of hogs and the braying of cattle.

In August, he flew to New York on his journey back to Groton.

It was while he was staying in Manhattan that Peter had a brainwave. He realised that his situation at Groton School would always be tenuous because permanent positions rarely occurred, save through death or retirement.

He decided, therefore, to set himself up as an ‘Alistair Cooke in reverse’. Cooke was an Englishman who had started his career as a correspondent with the Manchester Guardian. After he moved to America in 1937, he became the equivalent of a National Treasure, known for his weekly ‘Letters from America’ on BBC Radio, which were broadcast over a period of fifty eight years.

The formula was simple but unique and drew heavily on personal experiences of casual conversations with ordinary people. In 1952, ‘The Letter’ had just won a Peabody Award, radio’s equivalent of an Oscar.

Peter wrote Cooke a letter, outlining his idea of teaching Americans about England and Cooke invited him to his apartment on 5th Avenue for a drink. He was friendly, witty, entertaining and perhaps a little egotistical. If I want to go ahead with this, it will mean a clear cut policy and high pressure salesmanship.

In an attempt to widen the horizons of both students and faculty, Jack Crocker had begun inviting distinguished speakers to the school. Over the years, these included Eleanor Roosevelt, Martin Luther King, Robert Frost and, Reinhold Niebuhr. Peter decided to invite Alistair Cooke to speak to the boys and on November 11th, 1952, Cooke travelled the two hundred miles to Groton from New York. His talk was urbane and fluent – fluent to the point of glibness. All found him most entertaining.

The test of Groton is what its graduates will be like as human beings when they are your age and mine and even older.

Jack Crocker in a talk to the Faculty, April 1961

A Groton boy was deemed to be in service, both to God and his fellow man and the school has always challenged its students to assume the mantle of social responsibility.

Hiram Anthony Bingham, known as Tony, was Peter’s advisee and Dorm prefect and he taught Mr. O’Connell how to play a strategic game of chequers.

I was struck by the boy’s name and wondered whether he was any relation to Hiram Bingham, the explorer who discovered Macchu Picchu in 1911. Tony died in 2008 and his obituary is a template for the ideal Groton student. He founded a company promoting renewable energy and clean technology and was a generous supporter and patron of the Waldorf schools.

Tony Bingham’s grandmother was an heiress to the Tiffany fortune and his grandfather had indeed discovered The Lost City of the Incas. The Binghams, however, recognised that great wealth carried with it great responsibility.

Tony’s father, Hiram Bingham IV, known as Harry, was the US Vice Consul in Marseilles during WWII and in 1940, he disobeyed orders from Washington and issued more than two and a half thousand exit visas to Jewish refugees escaping to the United States. When the war ended, so did his career with the State Department.

Harry and his wife Rose, who worked as a school teacher, retired to the family farm in Connecticut and raised their eleven children, of which Tony was the eldest. It was not until Harry Bingham died in 1988, that the full extent of his humanitarian work during WWII was discovered. He was subsequently honoured by Yad Vashem.

For several years Jack Crocker had been giving serious consideration to the question of admitting African Americans to Groton. He was well aware that the school was not living up to its Christian ideals by limiting what it offered only to wealthy white boys.

In September 1952, Roscoe Lewis from Washington DC became the school’s first black student and his arrival, two years before the United States Supreme Court ruled that separate educational facilities were inherently unequal, made the front page of The New York Times.

In November 1952, Groton was back in the news when the Austin Motor Company launched an advertisement with the caption: I am sending my son to Groton on the money I saved by buying an Austin.

Jack Crocker was furious at this crude attempt to combine snobbery and economy at Groton’s expense.

Psychology was coming of age in the 1950s and many schools in America were appointing resident psychiatrists.

Reverend Crocker was reluctant to do this because he disagreed with Freud’s theory that religion was a neurosis and that man should rely, not on God for his salvation, but on himself and his own efforts. He recognised, however that Groton needed help and so he contacted Dr. Herbert Harris, a psychiatrist at The Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

If all masters were Mr. O’Connell, school would be a wonderful place

Mr. Kellog, quoting his son, Tony, in a letter to Peter

Peter remained committed to purposeful and relevant teaching. In October of 1952, he took a group of boys to hear Adlai Stevenson speak in Boston, stopping en route to buy them frappes at Howard Johnson.

A week later, he woke his dorm at one in the morning to hear the results of the presidential election.

In History classes, Mr. O’Connell used the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II to teach his students about seventeenth century religious conflict in Ireland.

In English, he recorded the boys reciting Hamlet’s soliloquies and then played them a tape of the same passages spoken by Laurence Olivier. Peter’s intention was to inspire but for some, the comparison served only to deflate. Parke Gray, son of the Bishop of Connecticut, so disliked the work in Mr. O’Connell’s class, that he complained to the Head of English and asked to be moved to another division.

My father was away a lot when I was growing up: teaching, learning and making the world a better place. He felt guilty about his frequent absences and so he sent me postcards. These invariably contained educational quizzes intended to improve my mind because a simple postcard would have been simply wasteful.

Unlike Parke Gray, I couldn’t move to another division; all I could do was refuse to give them my attention. I still balk at riddles. I simply will not engage them and I recognise, with some satisfaction, that my interrogator is entirely powerless in the face of my noncompliance.

Peter’s desire, both to educate and be popular, occasionally undermined his good judgment and, on the way back to Groton from a football game, he even put lives at risk: I meant to be sedate but when Fitz Hardcastle passed me I couldn’t resist the temptation to repass, travelling at one point at 65mph. This is too fast with boys aboard and with one worn tire.

Douglas Brown was a student at Groton in 1954 and Peter was his English teacher. Doug recalls asking Mr. O’Connell to raise his grade so he could remain on the honour roll. Peter agreed but Doug subsequently regretted his request:

Mr. O’Connell was the adult and the correct response should have been: This is the mark I believe you deserve and corresponds to your overall efforts and achievement. It will stand as it is.

He told me, a little sadly, that, following this incident, his relationship with Peter became more distant.

I saw Jack Crocker as a god-like figure.

Douglas Brown

In 2016, during an afternoon spent with Doug in the archives of Hundred House, I asked him about the changing nature of religious faith at Groton. It is no longer promoted as a Christian school and Sacred Studies has been replaced by Ethics. Some form of worship, however, is compulsory and Chapel remains mandatory four mornings a week:

You can claim you hate it said Doug, you can refuse to sing or say amen, but you’re in there, four or five days a week and, over time, it will have an effect on you. It becomes a spiritual experience, however you choose to interpret it.

It was through Jack Crocker that Peter first experienced religious faith as a source of consolation rather than punishment. Whenever his belief, either in himself or in God, began to falter, it was Jack who gave him renewed courage; it was talking to Jack that temporarily chased away the devil snapping at his heels.

The Reverend Crocker was a tall, imposing man with a hearty laugh. He wore a collar at all times, robes in chapel and was widely respected as a preacher. Sometimes he spoke to the inner world of the Groton boy; sometimes he spoke of the society that surrounded it, but his sermons were always relevant and important.

Jack’s intention was to prepare students and faculty to meet failure without losing heart and to handle success without being corrupted by it. These were particular issues that haunted my father. He struggled to accept the possibility of a middle way, one that might include both human and divine rapture. My faith in a hereafter is so very small, he writes in his diary.

Jack considered Peter to be essentially religious because he was attuned to the feelings of others, especially to the boys who struggled under the pressure of life at Groton.

An awestruck pupil at Highfield had once declared that listening to Mr. O’Connell read the gospel was like listening to Jesus himself.

In gratitude for Peter’s kindness to his son, Reinhold Niebuhr gave my father a signed copy of his book ‘The Irony of American History’. In his thank you letter, Peter took the opportunity to seek Niebuhr’s advice regarding his own religious hairballs and he received a thoughtful and gracious reply:

May 7th, 1952

Dear Mr. O’Connell,

I deeply appreciate your letter if for no other reason than it gives me an opportunity to thank you for your great kindness and help to Christopher.

I meant my copy of the book to be a token of my gratitude but it is a poor token indeed. I find as a matter of fact that parents are so deeply indebted to teachers who take an interest in their children that there is no adequate way of expressing gratitude.

The issues which you raise in your letter have concerned me all of my life, but I have reached rather different conclusions.

I believe, for instance, that in a world where, as Pascal said, justice must be enforced by power the voluntary abnegation of power by a few Christians is not as valuable as the wielding of power ‘with fear and trembling’ in the way that every business man and every Government official must wield it……. Whether on the question of powerlessness or poverty it seems to me that the Christian has to choose essentially between the Monastic-perfectionist principle of goodness and an essentially Protestant one.

According to the one he seeks to free himself from the evils of the world but he does not seriously affect the struggle in the world for a tolerable justice and brotherhood.

According to the other, he never escapes guilt because he is involved in all the various forms of guilt in the social life of man, but he regards this as a concomitant of ‘an ethic of responsibility’ in contrast to ‘an ethic of perfection’.

I know this is a very sketchy way of stating a very ultimate problem with which I have been wrestling, as it were, all my life.

With cordial, personal regards,

Reinhold Niebuhr.

Niebuhr spent thirteen years as a pastor in Detroit where he was highly vocal in his criticisms of Henry Ford and the American automobile industry in the days before labour was protected by unions. His own humility and lack of social pretension established him as a figure of enormous respect amongst politicians, students and civil rights activists.

Martin Luther King Jr. studied Niebuhr while he was writing his doctoral thesis and later praised him as a theologian of great prophetic vision. In 1965, King invited him to join the march from Selma to Montgomery and only a severe stroke prevented him from accepting the invitation.

Niebuhr is perhaps best known for writing ‘The Serenity Prayer’ which was later adopted by Alcoholics Anonymous.

A man is trapped in his home by rising flood waters. He stands on the roof of his house and prays fervently to God to rescue him. A boat sails past and offers to take him onboard, but he declines, saying: God will save me.

A little later, a helicopter flies overheard and the pilot offers him a lift: No thank you replies the man, I’m waiting for God.

Eventually, the man drowns and when he arrives before the Almighty, he complains bitterly: I prayed so hard and you didn’t help me, to which God replies: I sent you a boat and a helicopter.

It is a great pity that neither Reinhold Niebuhr, nor Jack Crocker, nor even the long shadow cast by the mighty Reverend Peabody could rescue my father from the turbulent waters of his evangelical childhood and the guilt and doubt that consumed his adult life.

He had the tremendous good fortune to meet two wise and principled religious thinkers who offered him a meaningful alternative. His religion, however, remained rooted, not in awe, not in wonder of God’s love, but in an unrelenting fear of punishment and eternity in Hell.

Soccer squad shaping up well. Kermit Roosevelt is a useful recruit.

Peter, diary entry, 1954

Between 1899 and 1961, twenty members of the Roosevelt family graduated from Groton. Kermit was the great grandson of President Theodore and Kermit’s father, Kermit ‘Kim’ Jr. led the 1953 coup in Iran which brought Shah Reza Pahlavi to power.

Groton’s most famous Roosevelt was undoubtedly Franklin Delano. An only child and used to solitary pursuits, he did not thrive at the school, although he later sent his eldest son John, to Groton.

In 1934, on the occasion of John’s graduation, Alan Pifer’s mother, Betsy, marched the then thirteen year old Alan up to FDR and said: ‘Mr. President, I would like you to meet my son, Alan’.

Betsy, like Sara Delano, had an intuition that her son was destined for greatness. Perhaps she hoped that one day, upon hearing the name Alan Pifer, the President might recall the day he had been formally introduced to the young Pifer at Groton.

Groton School is perfectly incomprehensible to those who have not belonged to it.

William Amory Gardner, teacher, 1884 – 1930.

I recognise that I have an idealised view of Groton School, due, in part to the fact that I have never belonged to its student body. It was, however, a close call.

In 1975, twenty three years after the school accepted its first African American student, Groton opened its doors to girls. It was around this time that my parents considered sending me to boarding school. The three contenders were A.S. Neill’s Summerhill, St. Christopher School in Letchworth and Groton.

In a letter, sent to me from Massachusetts in 1974, my father writes:

I have spoken to the Director of Admissions about you. He’s impressed! You’re too young for 1975 as a 6th Former but he’ll take you in 1976 for one year as a non-diploma candidate (no worry about exams!). Or, you can come next year as a 5th Former, stay for two years and take a Groton School Diploma (very highly regarded).

I have just seen the Groton film – if you saw it you’d be lining up for a place! All those handsome boys and lots of fun amongst the hard work.

I am astonished by Peter’s liberal use of the exclamation mark, a form of punctuation he generally considered to be a sign of lazy writing!

My father was enthusiastic about the possibility of my going to Groton but my mother was dead against it. She said I’d fall in love with an American and never come back to England, which, to me, felt more like a promise than a threat.

Twenty five years later, when my former husband was offered a position with an American watch company in New Jersey, I wrote to the headmaster and inquired about the possibility of enrolling our daughters at Groton.

Bill Polk had been a pupil of Peter’s and expressed delight at the prospect of Two O’Connells walking the hallways of Hundred House. In the end, we moved to London and the girls became day pupils at St. Christopher School in Letchworth.

There is, of course, another side to Groton.

Alan Pifer, honoured as a Distinguished Grotonian and a guest speaker at the school’s one hundredth birthday, had been unhappy at Groton and chose to educate his three sons elsewhere.

Amos Booth, who spent three years as a bachelor master at Groton in the mid 1950s and returned in 1973 with his young family, wrote many years later:

More than did your father, I ran across a disaffected minority who were – and remain – victims, unsung, and still hurting.

Foremost on my list and conscience are my own children, hapless victims of my benighted ignorance and witness to my involvement in the lives of other people’s children. In the ‘old days’ faculty brats were farmed out to other boarding schools.

Amos’ wife, Jeannine grew to hate Groton. In 1978, in a letter to Peter, Amos writes: Nanie is working for $3 an hour in a dress shop which at least gets her out of the incestuous atmosphere of the ‘family school’ and its hallowed halls.

Peter arrived at Groton in 1951 to replace ‘Zu’ Zahner who had gone to Beirut for a year to teach at the American University. Every spring, Peter, and others like him, would wait for notification of available positions for the following year and, if a post suited a master’s skill set, he could apply.

During my father’s four years at Groton, he taught English, History, German, Latin and American Government but, in 1955, there were no suitable vacancies and he had to seek a position elsewhere.

Year 5 dedicated the 1955 Groton School year book to Mr. O’Connell. His unselfish dedication and guidance will be sincerely missed by us and by the school.

Peter moved to Dedham where he taught for a year at Noble and Greenough School before returning to England in 1956.

In the spring of 2017, I travelled to Massachusetts with the intention of digging deeper into the mystery and the magic that is Groton School. I arrived at eight o’clock on a May morning, expecting to negotiate locked gates and an intercom system but there was only Herm, the security guard, standing outside the chapel.

He listened with interest to my story and then said: ‘Well, if your Dad was here in the 1950s, then you best talk to Mr. Sackett. He’s coming up the path behind you’.

Hugh Sackett had arrived at Groton the year my father left but had visited my parents in England.

The Chapel Talks at Groton have become a rite of passage for students in their senior year and the best ones are published in the Groton School Quarterly. I heard three talks during the four days I spent on campus and was surprised by their revelatory content. School policy is not to censor, nor even to read the chapel talks in advance.

The Groton hallmark, however, remains: life isn’t simply about following your heart, it’s about using your silver spoon to live a life that has purpose and meaning.

After chapel, I sat for a while on a bench outside Schoolhouse. The hot pinks and soft corals of cherry and rhododendron blossomed beneath a cobalt blue sky and, as the sunlight hit the white porticos and the golden cupola, I experienced a great yearning to step back in time and walk into my father’s long ago life at Groton.

During the four days I spent on campus, I sat in on a History class, joined the students for milk and cookies in The Sackett Forum and toured the dormitories of Hundred House. The wood panelled cubicles with their single beds are long gone and the dorm masters’ studies and bedrooms have been converted into student lounges.

On the day I returned to England, I thought again about all the stories my father had so lovingly shared with me as I was growing up, stories which I had embellished in my own imagination.

Groton, although alien in many ways, is not perfectly incomprehensible to me.

My father’s love affair with the school has become mine and, as long as I live, I believe I shall view Groton as practically perfect in every way.

Excerpts from:

The Absent Prince: In search of missing men by Una Suseli O’Connell

pub. Conrad Press, UK, June 2020